Blue Highways: Kennebunkport, Maine

Unfolding the Map

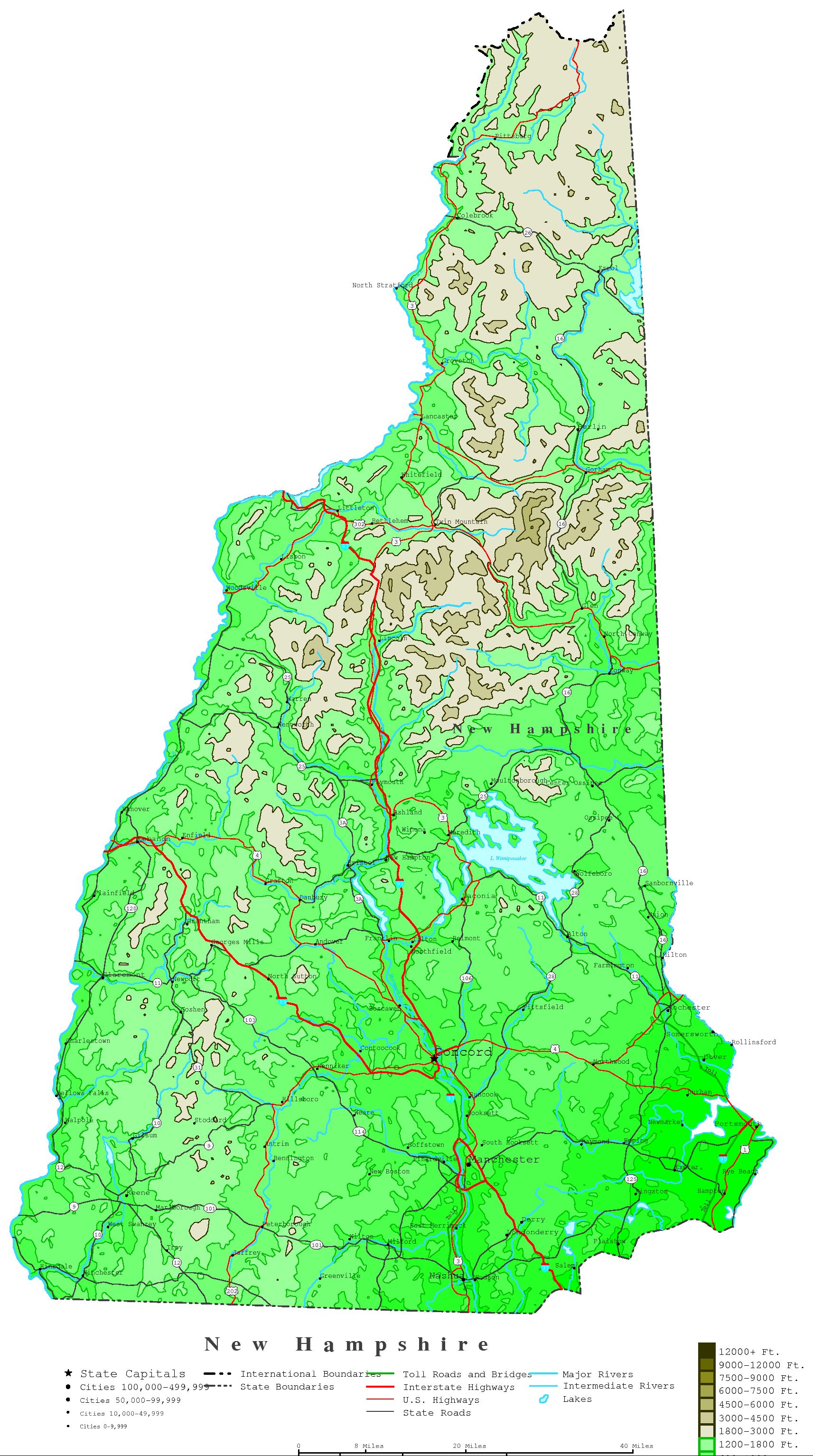

We pull into the Atlantic seaside town of Kennebunkport, Maine with William Least Heat-Moon (LHM). I doubt we'll be able to have a beer with Dubya, or hang out with George Senior and Barbara, but we can explore the place with LHM a little while and reflect on going behind the facades of towns and cities. To see where Kennebunkport's pretty face and place is located, sashay over to the map.

We pull into the Atlantic seaside town of Kennebunkport, Maine with William Least Heat-Moon (LHM). I doubt we'll be able to have a beer with Dubya, or hang out with George Senior and Barbara, but we can explore the place with LHM a little while and reflect on going behind the facades of towns and cities. To see where Kennebunkport's pretty face and place is located, sashay over to the map.

Book Quote

"I did what you do in Kennebunkport: walk the odd angles and sudden turns of alleyways and cul-de-sacs among the bleached shingled buildings, climb the exterior stairs to the old lofts, step around lobster pots and upturned dinghies."

Blue Highways: Part 9, Chapter 2

Dock Square in Kennebunkport, Maine. Photo by Eric H. and hosted at VisitingNewEngland.com. Click on photo to go to host page.

Dock Square in Kennebunkport, Maine. Photo by Eric H. and hosted at VisitingNewEngland.com. Click on photo to go to host page.

Kennebunkport, Maine

I love exploring places. There's nothing better for me than poking around, putting my nose into things, and trying to discover not only what a place might want you to see, but those other things that don't generally get put front and center.

I once read a phrase about traveling by train that has stayed with me forever. I read, regarding the difference between car and train travel, that in a car you are often shunted by towns on an interstate. If you end up going through a downtown you see the best the town has to offer - the storefronts, plazas, parks, and the best houses. Often either side of the town is framed with the storefront strips which may not be aesthetically pleasing, but which offer you the things you want and need. In other words, the highways bring out America's Sunday best combined with the practical.

On a train, the article argued, you will enter a town through the back ways.. You often travel through the less desirable parts of town, where there are empty warehouses and where the houses have either lost their luster or are completely dilapidated. Sometimes this is so apparent that when you get off the train in the downtown you wonder if you are in the same place. If driving is seeing America's towns and cities at their prettiest and most presentable, the article argued, then often taking the train is like seeing America's towns and cities in their underwear, sitting on the sofa and scratching themselves and wondering where the glory days have gone.

In other words, just like people, American towns and cities put on facades. Sometimes the facades are physical. In my hometown, for example, a lot of the historic buildings had or have false storefronts built up high to resemble two-story buildings. They aren't. The buildings are really are one story and you see this if you observe any of those buildings from the side and can see the facade. Sometimes the facades are the public faces that cities and town put on. For example, a town in Iowa celebrates its Dutch heritage with windmills and tulips, while other towns point your attention to art and culture. It is similar to a man slapping on aftershave and a tie, or a woman wearing a nice dress and makeup.

Perhaps such finery is nice, but at the risk of seeming like a pervert, I kind of like the underwear.

I like exploring in the places that are, purposely or not, where a lot of people don't go. Don't get me wrong. When I visit a town I enjoy walking along the main streets and going in and out of the shops. I like hanging out nicely dressed once in awhile with others who are dressed to impress, I enjoy looking at what towns and cities want us to see. At least for a little while.

Then, I go looking for the other stuff. What is down that back alley? What might I find on the "wrong side of the tracks?" Many times, I find nothing. Many times there is nothing to see. But sometimes...

Sometimes you find little things. A small museum that hardly anybody visits. A little store that has interesting and strange knick-knacks. A person who is willing to talk about what he or she remembers about the town or city history. A character that is immensely entertaining. Perhaps you will be invited into see a house that has an interesting history, or some qirk that you might never see anywhere else. Sometimes, you might even chance on an element of the seedy, even risky. I try not to get into places where it is too risky or too seedy, though one can always find oneself in such places if one is not careful.

The characters, the quirks, and the interesting happenings are few and far between. Many times you find nothing. But the point is, unless you "walk the odd angles and sudden turns of alleyways and cul-de-sacs among the bleached shingled buildings, climb the exterior stairs to the old lofts", you're never going to have a chance to see such places or meet such people.

Now, there are some people who, inexplicably to me, are not interested in the "out-of-the-way" or "off-the-beaten-path" places. There are those who prefer the chain restaurants because they know exactly what they will get to eat. They prefer the malls and the familiar types of shops found in every place across the United States. The familiar is comforting and takes away uncertainty.

That's not me. If there's a new food to try in a new place that I've never heard of, I'm there. I may not like it, but often it's simply the experience that is the reward, not whether I actually like it or not. If there's a strange shop or museum, I'm there. This yearning to find the absurd, the interesting, and the strange is what has led me to such amazing little places like the Museum of Jurassic Technology in Los Angeles, little out of the way, unorganized or organized small-town museums with stuffed two-headed calves and every little item donated by town patrons for a hundred or more years. It led me to the Bone Lady in New Mexico. All of these experiences enriched me in one way or another. It led me to love the surprises that our lives and journeys sometimes throw at us if we are willing to go to places that we might never have considered.

When you see a lonely road going somewhere into the hills, do you have an urge to explore it? Are you always wondering what comes around the next bend? Are you willing to explore the back alleys of a town or city. If you see a person who is doing something you don't understand, is your inclination to stop and question them? If you see a sign for a roadside attraction that seems a little strange, do you pull off to see it? If so, then you know what I'm writing about. You understand that sometimes, if you get behind the scenes, venture behind the curtain, there are wonderful things to be seen and experienced.

Which brings me back to Kennebunkport. You can spend time seeing the shops, hanging out on the beach, or visiting the Bush family compound (if you're a VIP or a friend of one of the George's), and that's all good. But, as LHM points out in the chapter, give me the small and out-of-the-way eateries on the south side of the river too. You can visit a locality, but it's often special to find, taste, touch and live what's truly local, ungussied, unvarnished and therefore, utterly real.

Musical Interlude

I didn't read Coraline or see the movie, but this song called Exploration from the movie, sung by a childrens' choir and complete with nonsensical lyrics, seems to encompass the lightheartedness but also anticipation of exploration. I doubt LHM had this type of tune going through his head when he explored Kennebunkport, but he could have!

If you want to know more about Kennebunkport

Kennebunkport.com

Kennebunkport Chamber of Commerce

Kennebunkport, Maine

Town of Kennebunkport

Wikipedia: Kennebunkport

Next up: Cape Porpoise, Maine

Thursday, July 19, 2012 at 4:10PM

Thursday, July 19, 2012 at 4:10PM