Blue Highways: Melvin Village, New Hampshire

Unfolding the Map

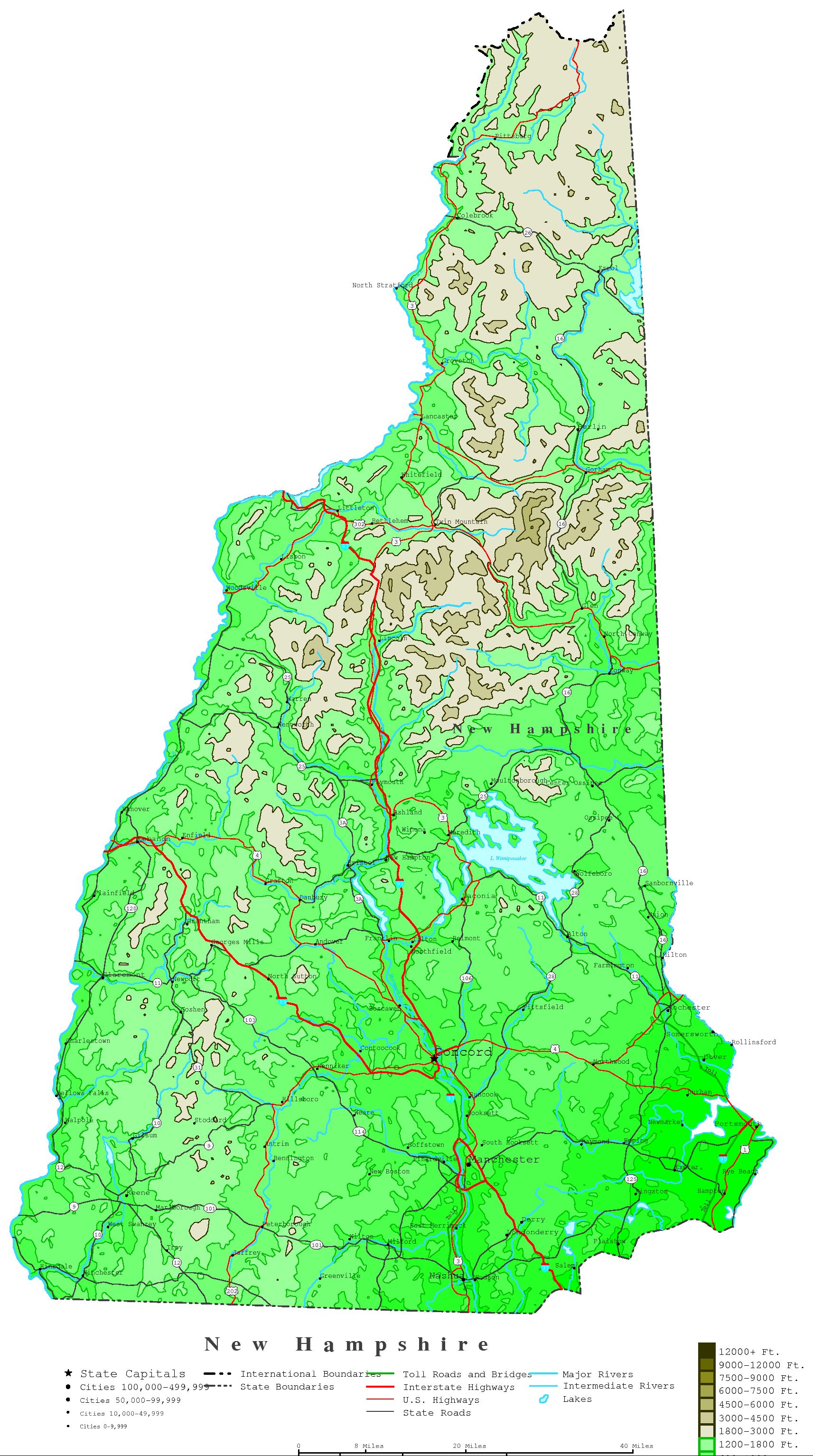

The Blue Highways quote below, about an elderly resident of Melvin Village who helps William Least Heat-Moon see, through her long years of perspective, that change is constant and a recurring, cyclical happening, leads me to reflect on the influence of the elderly residents of my hometown on the fabric of its social structure. To age gracefully in Melvin Village, pass some of your precious time at the map.

The Blue Highways quote below, about an elderly resident of Melvin Village who helps William Least Heat-Moon see, through her long years of perspective, that change is constant and a recurring, cyclical happening, leads me to reflect on the influence of the elderly residents of my hometown on the fabric of its social structure. To age gracefully in Melvin Village, pass some of your precious time at the map.

Book Quote

"Marion Horner Robie had not been Melvin Village for all her eighty years; the first seven decades she was just another citizen of fewer than five hundred, although when she ran the post office, grocery and dry goods store, telephone switchboard, and the fire dispatch all at the same time, she was (admittedly) 'the big cheese.'....

"....In broad New England vowels, Mrs Robie said: 'I never planned on becoming the big cheese, you see. It fell about that way as chance does...'"

Blue Highways: Part 8, Chapter 11

Melvin Village, New Hampshire from Lake Winnipesaukee. Photo at the Melvin Village Soy Candles website. Click on photo to go to host site.

Melvin Village, New Hampshire

When I map a book like On the Road or Blue Highways, both geographically or cognitively, I never quite know where the cognitive topography will take me. In this post, I am going to a place that surprises me.

It shouldn't be so surprising. After all, LHM meets a woman who, partly because of her advanced years, has become the self-described "big cheese" of Melvin Village, New Hampshire. To me, age really defines those who actually are the big cheeses from those are "wannabee" big cheeses or who think they are big cheeses.

With that awkward beginning, I now get to my point. I grew up in a small town, and there one always can find those people who, because of their age, have reached a lofty status among the rest of the people in the town. These people are the town elders, whose major accomplishments have been to live and experience and to reach a point where they can pass their experience, history, memories and wisdom to the generations behind them. Every culture that I can think of puts older people into a class reserved entirely for them. Somewhat removed but always sought out in case of crisis. A recent viewing of The Seven Samurai by the great director Akira Kurosawa reminded me of this common instinct in our cultures. In the movie villagers, tired of repeated attacks by bandits, consult the oldest man in the village to ask him what they should do. His advice, hire seven samurai to defend the village from the next expected attack, is heeded and with the aid of the samurai, the villagers repel the attackers.

Gertrude White never had to give such advice to my hometown residents, though I had no doubt that she would have if needed. Actually, I have no doubt that she would have led the defense if the village was attacked. From the day I first remember her, when I was perhaps three or four, to the day that she died, she always seemed old to me. She owned a stretch of land along Airport Road, an unknown number (to me) of acres that once served as the town airport for which the street was named. I think I was only in her house once, however we always had some kind of contact with her. She ran a horse riding club. My grandmother, who was a good friend but who I believe also looked up to Mrs. White as a mentor often rode horses with her in the local Paul Bunyan Days parades. My grandmother was perhaps 10-15 years younger than Mrs. White, but I think their shared history of growing up and living in the area brought them together and, as their ages became greater the difference between them grew less and less.

As the matriarch of the horse club, Mrs. White touched the lives of a lot of young children, mostly girls. Our summer weekends often revolved around her horse shows, in which manes and tails tore around barrels or ripped around the track at breakneck speed with very fragile little girls clinging to them. But I remember that Mrs. White was also heavily involved in town business and affairs, and can think of a couple of times when I heard of residents of my parents generation approaching her for advice or to learn some history about how the town handled certain situations in the past. As she got older, her mystique, augmented by her large house, seemed to grow. When she died, somewhere approaching 100 years old, it was like the passing of an era that we could never get back.

My grandmother, Mary Cox, was very similar. She was something of what I considered the last of the pioneers of Northern California. She grew up in the woods where her father and grandfather ran a small lumber mill. She married a fisherman who turned lumberman in the depression, and then reverted back to fisherman. She raised four children (one of which was my mother) in logging camps in the woods during the heart of the Great Depression. After her husband died of cancer when she was in her fifties, she used it as an opportunity to get the education she always wanted but never had, and got her nursing degree. She worked until she was into her seventies and forced into retirement because of a back and knee injury sustained while trying to hold up an unsteady and heavy patient.

My grandmother was the focal point of our family. Our lives, especially as she got older, revolved around her. My sisters and cousins spent afternoons after school and entire summer days over at her house riding her horses. Family members went to her for advice, and often received blunt words from a woman who had seen almost everything in her life and knew that the solution to life's problems began with the person who was having them. Sometimes family members, as she got older, tried to keep news from her of certain family members' bad behavior, or problems that arose within the family. It didn't matter - she always seemed to know anyhow. I often went to talk to her to hear first-person accounts stories of growing up and living in places and times that otherwise I would only be able to read about. My grandmother was also, for a time, the only one of our family that had traveled to Europe, and her accounts of visiting her relatives in Austria fascinated me and fueled my own desire to travel to other places.

When my grandmother died in her mid-nineties in 2001, her passing was like the breaking of the cement that held disparate elements of the extended family together. Her children, my mom and her remaining siblings, still come together for the holidays but the spark that fed them, my grandmother, is missed.

If you view a small town as an extended family, the influence, wisdom, history and common-sense that our elders provide is incalcuable. It is no accident that it seems that in smaller locales that elders are held in the most esteem, and valued more. In large cities, it is easy enough to become lost in the teeming masses, and I think that older people are often forgotten in those places where the business of life often takes precedence over the relations and the connections that we need. Our policies, which make it harder for our older members of society to live and get by, also do not help.

I have learned, however, that there is no substitute for an older, wiser presence in our lives. We may not agree with everything our elders say and they can be as wrong as anyone else. I would argue that isn't the point. When they speak with us, we are almost compelled to listen, and it is in our listening that we give ourselves the space to come to our own wisdom and solutions. I wish I could thank my grandmother for those times that she made me stop, think, and take stock, whether or not her views were useful to me or not. Just her presence was sometimes enough.

Musical Interlude

The Who's My Generation was originally about the younger generation telling the older generation where it could go and what it could do to itself. It's pretty amazing that this group of older people, The Zimmers, have turned that song on its head. Now they're doing the singing, and telling the rest of us where to go. Good for them!

I also had to include Neil Young's Old Man, that melancholy air that shows that young people and old people often have the same needs.

If you want to know more about Melvin Village

Sorry, there's not too much on Melvin Village.

Next up: Hunter's Maple Farm, New Hampshire

Tuesday, July 10, 2012 at 10:08PM

Tuesday, July 10, 2012 at 10:08PM