Blue Highways: Roosevelt, Whitcomb and Paterson, Washington

Unfolding the Map

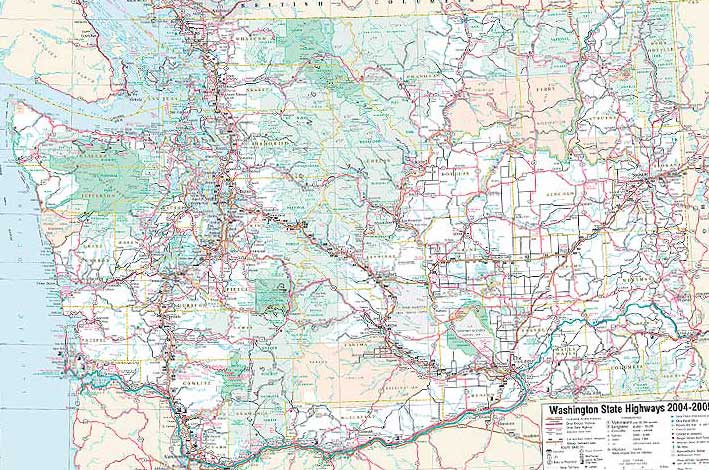

We are riding and clenching our buttocks with William Least Heat-Moon (LHM) as we hope to find a gas station somewhere along the Columbia River in Washington before we have to get out and walk. Have you ever run out of gas, or almost run out of gas? Feel free to leave a comment if you have. If you want to see where all this butt-clenching is taking place, go to the map.

We are riding and clenching our buttocks with William Least Heat-Moon (LHM) as we hope to find a gas station somewhere along the Columbia River in Washington before we have to get out and walk. Have you ever run out of gas, or almost run out of gas? Feel free to leave a comment if you have. If you want to see where all this butt-clenching is taking place, go to the map.

Book Quote

"On the highway again: at a cluster of closed buildings called Roosevelt, I noticed my gas was low. The next town, according to the atlas, was Moonax five miles away. Ten miles on, McCredie; fifteen, Alderdale; twenty, Whitcomb. I drove unconcerned. But Moonax was another Liberty Bond. Same with McCredie. Down went the needle. I could see stations along the interstate a mile south across the bridgeless river. No Alderdale. I locked the speedometer needle on forty-five and my arms to the steering wheel. A traveling salesman once told me that if you tense butt muscles tight enough, you can run on an empty tank for miles. And that's what it was going to take. Whitcomb was there, more or less, but the station was closed on Sundays. Paterson, the last hope. If it proved a ghost town, I was going to learn more about this deleted landscape on foot. I drove, tensed top to bottom, waiting for the sickening silent glide. Of the one hundred seventy-one thousand gas stations in the country, I needed one."

Blue Highways: Part 6, Chapter 10

Biofuel crops in Paterson, Washington. Photo at Washington State University's Biofuels Cropping Systems Research and Extension Project's site. Click on photo to go to site.

Biofuel crops in Paterson, Washington. Photo at Washington State University's Biofuels Cropping Systems Research and Extension Project's site. Click on photo to go to site.

Roosevelt, Whitcomb and Paterson, Washington

We've all been in LHM's position, haven't we? We're driving down a stretch of freeway, no exit in sight, and the needle on the gas gauge (or the digital graphic readout) is actually below the empty line. We are tense, hoping that over the next small rise, or around the next corner, we will see our salvation in the form of a road sign that tells us that in one mile we'll find gas, food and lodging. Or perhaps, peeking over the trees, a Conoco or Shell or Valero or some other gas station sign.

We've all been in LHM's position, haven't we? We're driving down a stretch of freeway, no exit in sight, and the needle on the gas gauge (or the digital graphic readout) is actually below the empty line. We are tense, hoping that over the next small rise, or around the next corner, we will see our salvation in the form of a road sign that tells us that in one mile we'll find gas, food and lodging. Or perhaps, peeking over the trees, a Conoco or Shell or Valero or some other gas station sign.

I used to drive on a lot of out-of-state trips on a job I had. I would go from Wisconsin to New York, or perhaps down to the DC area, or to Philadelphia. And I must admit that I was not one who was very risky when it came to gas. If I noticed the needle down to, oh, lets say an eighth of a tank I would find the next gas station and fill up. However, when you're driving roads you don't know, the problem is one of making the right choice mixed with a little bit of luck. At the time I was traveling, in the early 90s, the internet was in its infancy. Cell phones were huge contraptions with big antennae that only wealthy people or government workers in security agencies used. Atlases and road maps were all we had to inform us of what was ahead on the road. If it was on the map, then it should be there.

But if you're LHM, or me at that time, you liked to take drives along the blue highways instead of the interstate. And that meant taking some risks. Because, like LHM, you might find that the map was wrong and a listed town was actually not much or worse yet, it folded up some years before leaving behind a collection of morose, empty and rotting buildings. Because I wasn't much of a risk taker, I would actually fill the tank more often during these times, so I wouldn't find myself out of gas on a lonely stretch of road where I might have to wait. In winter, this was even more imperative. The last thing I wanted to do was freeze to death in my car.

But despite my planning, I too had a few sphincter-tightening moments where I wondered if I'd make it. It usually involved being on a blue highway, and it usually occurred in a very rural, if not forested, area where there were few settlements, and often on a Sunday. I can remember, butt clenching rhythmically as I drove past small town after small town where either there was no gas station or the station was closed. I would longingly look at the pump and wonder if I could shake out a few drops from the bend in the hose that would get me perhaps a few feet farther down the road. I'd then hope for the best and drive for the next town. If I saw a sign for an interstate, I would head down that way because chances were better that a gas station might be at the junction and, because people traveled interstates on all days, might actually be open, Sundays be damned. I can remember at least two below-the-empty-line moments where I was sure I would experience, as LHM puts it, "the sickening silent glide." But it never happened.

In the pantheon of risk and reward, riding on empty is probably not as high up the chart as, let's say, summitting Everest or surfing a monster Hawaiian wave or hang-gliding or jumping out of an airplane or even heading out to hike in the woods on a day that looks like it might become vaguely threatening. And today the level of connectivity we have has made it even less risky. Looking for gas? You probably have an application on your sleek new Android phone or your handy new IPhone that will tell you where all the open gas stations in a fifty mile radius lie and direct you by synthetic voice along the shortest path to the place. It'll even tell you the price and may, because you used it, get you a discount in the convenience store on your favorite bag of chips. Out of gas? Just call your auto club of choice on your cell, or I just found out, if you are out of cell range you can buy a device that allows you to turn your cell phone into a satellite phone and it will use your GPS to guide your would-be rescuer to you.

But where's the fun in that? Where's the sense of adventure and thrill, when you drive into a gas station on the last remaining fumes of your previous 87 octane purchase, that you beat the odds once more and lived through something slightly dangerous? Something that might have made you get out of the car and depend on the kindness of strangers to get you to a gas station where you could purchase a gallon in a plastic jug and then find a ride back to your car so that you could get a few more miles back to the gas station.

I was always a lukewarm watcher of Seinfeld, because I had a love-hate for the characters who seemed to me to be spoiled and whiny even as I thought the plots were clever. If you'll remember, each show usually had 3-4 story arcs going through them that all tied back together at the end. In one story line in an episode, the character of Kramer is test driving a car with a dealer representative, and the car is on empty. (to see the clips from this episode relating to this story arc, click here.) They choose to see just how far they can go, if they can push the needle farther below empty than anyone ever has. At one point, the salesman says that the experience has expanded his horizon more than anything and has given him a heightened sense of what's possible. After all, we are at our best in our work, thinking and problem solving when there's a little risk involved.

Musical Interlude

I can't think about this topic without Jackson Browne coming to mind. Browne's music was a staple during my junior high, high school and college years. This is a nice live acoustic version of his song Running on Empty, though in the video the sound appears to be slightly off from his performance. Still, it's a great song and would have been relatively new when LHM was driving around the U.S. I bet he probably heard it on the radio in Ghost Dancing while he traveled.

If you want to know more about Roosevelt, Whitcomb and Paterson

Columbia Crest Winery (in Paterson)

The Columbia River: Paterson Ferry

The Columbia River: Roosevelt

The Columbia River: Whitcomb Island and Whitcomb

Wikipedia: Paterson

Wikipedia: Roosevelt

Next up: Umatilla, Oregon

Monday, November 14, 2011 at 5:48PM

Monday, November 14, 2011 at 5:48PM