Unfolding the Map

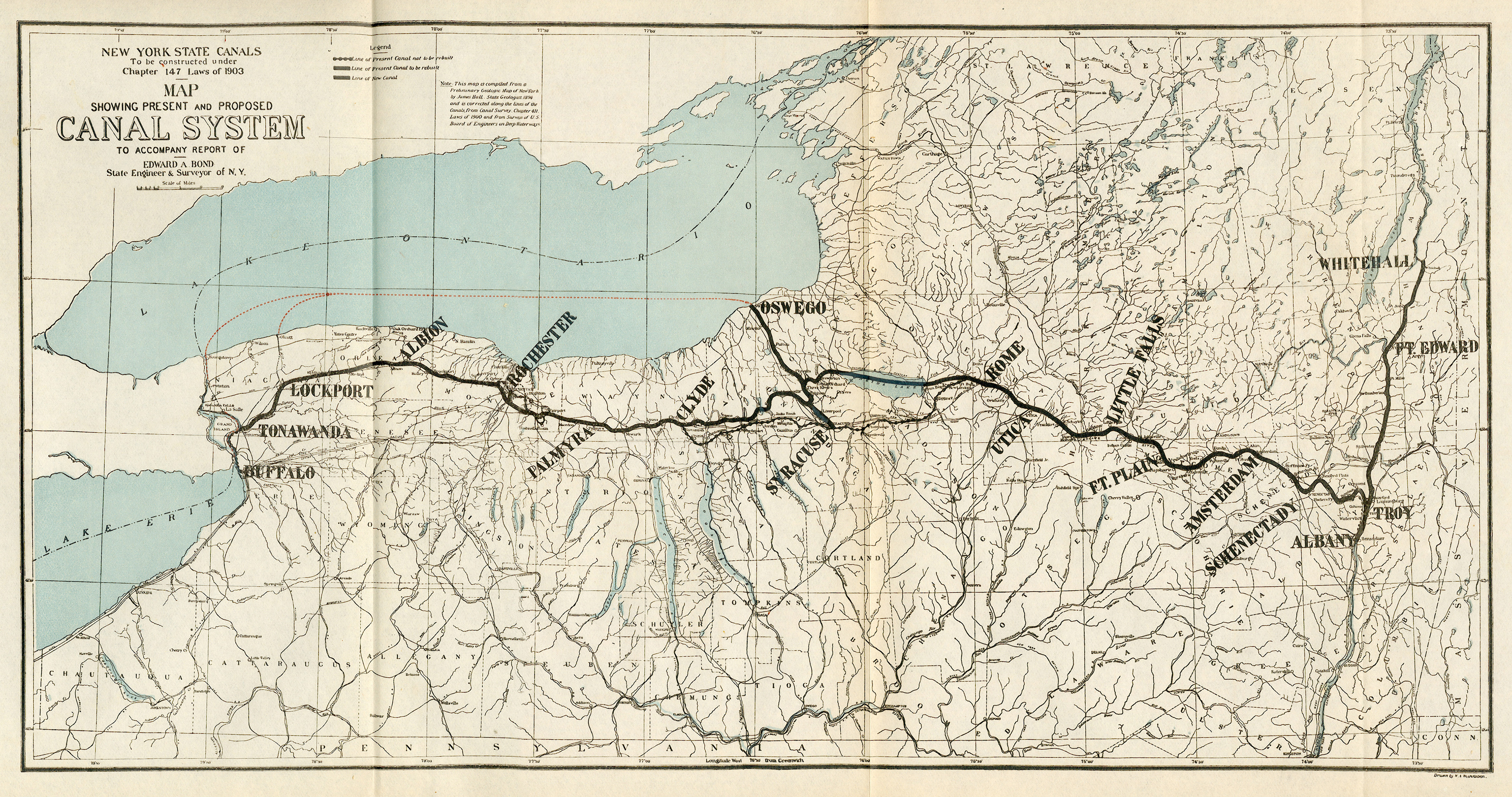

The Erie Canal is huge. Not necessarily in dimensions - it was only four feet deep and often just 40 feet wide, though it does span 363 miles from end to end. However, it is really huge in that it was an massive government public works undertaking, criticized and ridiculed, that paid for itself in a short amount of time and contributed in countless ways to the development of the United States. Stand with William Least Heat-Moon (LHM) on the edge of the canal, imagine the packet boats filled with people and barges filled with goods towed by mules and horses, and learn more about this amazing piece of our history. To find my approximation of where LHM stops at the canal, duck your head at the low bridge as you travel to the map.

The Erie Canal is huge. Not necessarily in dimensions - it was only four feet deep and often just 40 feet wide, though it does span 363 miles from end to end. However, it is really huge in that it was an massive government public works undertaking, criticized and ridiculed, that paid for itself in a short amount of time and contributed in countless ways to the development of the United States. Stand with William Least Heat-Moon (LHM) on the edge of the canal, imagine the packet boats filled with people and barges filled with goods towed by mules and horses, and learn more about this amazing piece of our history. To find my approximation of where LHM stops at the canal, duck your head at the low bridge as you travel to the map.

Book Quote

"The canal, only four feet deep in its early years, had become a rank, bosky froggy trough. But it was that forty-eight inches of water that did so much to open western New York and the Midwest to settlement and commerce....

"From Lake Erie to the Hudson River (363 miles, 83 stone locks, 13 aqueducts) the canal moved people and things between the middle of the nation and the ocean; it was this watercourse, as much as anything else, that made New York City the leading Atlantic port. Travelers who had some money could take a packet boat with windows and berths, while poorer immigrants heading into the Midlands rode cheaper and drearier line boats. Ten years after Clinton's Folly opened, the populations of Syracuse, Rochester and Buffalo increased three hundered percent; the canal, having paid for itself in that decade, had changed the northwest quarter of America. No paltry accomplishment for a scheme that even the visionary Thomas Jefferson saw as a little short of madness."

Blue Highways: Part 8, Chapter 6

The Erie Canal near Rome, New York. Photo by "genewest" and hosted at Panoramio. Click on photo to go to host page.

The Erie Canal near Rome, New York. Photo by "genewest" and hosted at Panoramio. Click on photo to go to host page.

Somewhere on the Erie Canal

When I was in grammar school, we still had some music education in the public schools. It didn't happen often, maybe once a week, but it usually involved some kind of percussion playing and/or singing. I think we had a guest teacher who would come in and lead these sessions.

I remember that the song book with which we worked had patriotic songs, and I remember that there were a couple of folk songs in there that I liked, but which I can't really remember so many years distant. John Henry might have been one of them, or at least it comes to mind.

The one snippet of song that I remember from that book is this:

Low bridge, everybody down,

Low bridge, 'cause we're comin' to a town.

And you'll always know your neighbor,

You'll always know your pal,

If you ever navigate upon the Erie Canal.

Why I remember this one lyric, I can't say. After all, there were more recognizable songs in that book. There were other tunes in that book that were fun to sing. Yet I've always kept that lyric about the Erie Canal in my head.

The Erie Canal is one of those massive efforts in our history that shouldn't be forgotten, but the benefits of which are not often considered. The concept was simple - create a waterway that joined a major river system with the Great Lakes so that development of the middle of the country could proceed. The execution was anything but simple. This waterway had to traverse over 363 miles of country with a total elevation rise of 600 feet, entailing inventiveness and the practical application of engineering that had never been used before. The sum estimated to build it was considered to be almost unimaginable. Even Thomas Jefferson, the man who sent Lewis and Clark into the interior with an instruction to look for woolly mammoths and giant sloths, thought that the project was practically insane for the time period.

Even so, it was taken up by the New York legislature and passed. The canal became known as Clinton's Folly (after Gov. DeWitt Clinton of New York) and was widely expected to fail. Yet it didn't. It employed thousands of people in the construction, particularly recent immigrants in need of work, and many of whom died of disease in marshes. At the time, the United States had no civil engineers, so it literally created the practice of civil engineering in the country. The builders of the canal, with no practical experience, had to solve problems like marshes and escarpments that stood in the way of joining the Hudson River with Lake Erie. The Canal also utilized new inventions, like hydraulic cement, to solve problems such as leaks.

How did the Canal work? Draft animals such as mules or horses pulled barges and packet boats by walking along a towpath alongside of the canal. There was only a towpath on one side of the canal, so when boats met each other, one draft animal would move toward the canal side of the towpath and the other toward the far side of the towpath. The mule or horse team at the far side would stop and let the boat float, causing the towline to go flat, and the other team would step over it and continue on.

This was a public works project that yielded enormous benefits to the benefits to the fledgling nation. American inventiveness and ingenuity were suddenly the envy and marvel of the world. New York City became the preeminent port on the Atlantic, spurring competition in cities like Baltimore and Philadelphia. According to A.K. Sandoval-Strausz, in his comprehensive history of the hotel, the increased opportunities of transport led to a rash of hotel building throughout the United States. Some estimate the Canal led to savings in transport costs of up to 95 percent. People and goods had to travel by animal drawn wagon before the Canal was built. If you consider that it was estimated that a team of four horses could pull one ton twelve miles to eighteen miles a day, depending on the road, but 1000 tons for 24 miles over water, you can see just how effective the Canal was in increasing commerce into the interior. The accompanying surge in population to the Midwest was an added benefit to a country that saw itself with a Manifest Destiny.

I am intrigued, in this day and age when government spending on public works is attacked as wasteful, how much good this governmental outlay of capital on such a project caused so much good. We are in a period where government can do no right, and certainly there were many doubters about the Erie Canal, yet the expense worked to the betterment of the nation. I am especially intrigued because, probably even more than now, the country had an immigrant problem. Hundreds of thousands of immigrants were flocking to the United States and settling in slums in major cities. The construction of the Erie Canal allowed them to find work, as well as moving them out of the slums and into areas where they could settle.

In New Mexico, the state government is almost finished on a project called Spaceport America. I almost see the idea as being analogous to the Erie Canal. As the federal government ramps down its spending on NASA, there is a push for private industry to step in and fill the gap by providing service to the International Space Station and other space initiatives. There is also expected an accompanying rise in space tourism. When my wife and I took a tour of the Spaceport facilities, the tour guide was positively gushing about the private sector role, and very negative about government. The message was that government doesn't do any good, and should stay out of the private market. My wife was moved to remind him that without government spending, the Spaceport would not have been built at all, and that government spending can often spur additional private spending. The guide then modified his rhetoric to agree, but then argued that government should then get out of the way.

As I see all the problems facing this country as I write, including a crumbling infrastructure, a large unemployment rate, and questions about immigration, I see a place for government spending. I may be revealing my political stripes, and readers are free to disagree, but of course I live in a state that lives or dies by government spending on military bases and research, federal lands, and reservations. But, it is very telling to me that some of the United States' biggest accomplishments could only come about by government being willing to spend money where a need was perceived, often regardless of how that expenditure was seen by the public, and often with spillover results that yielded benefits beyond the initial project. I'm willing to admit that government is not always positive, but often it is. Just look at the Erie Canal and its place in our history.

Musical Interlude

The Erie Canal song was written by Thomas Allen in 1905 after Erie Canal traffic switched from draft pulled barges to engine-powered barges. It is a piece of nostalgia about loss of a way of life and change in an increasingly mechanized society. In this version that I found, the song is performed by no other than Bruce Springsteen, off his tribute to Pete Seeger in his album We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions. The song was recorded live in Dublin, Ireland which adds an additional link - at the time many Scots-Irish immigrants to the United States were employed in building the canal (there is also a recording of Springsteen doing the song in Belfast, Northern Ireland which would have been even more appropriate, but it is not as good as this recording). This is the song that I sung in grammar school, but probably not as good as Springsteen and his band.

If you want to know more about the Erie Canal

Building the Erie Canal

The Erie Canal: A Journey Through the History

Erie Canal Museum

Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor

History of Building the Erie Canal

History of the Erie Canal

New York State Canals

Scenic Historic Erie Canal Sightseeing Cruises

Wikipedia: Erie Canal

Next up: Rome, New York